User:Bleff/sandbox8

Western fashion in the 1930s was characterized—in womenswear—by a departure from the boxy, boyish look from the previous decade in favor of a more mature and feminine silhouette, with the return of natural waistlines and a heightened emphasis on glamour, elegance and sophistication.[1][4] The era is well framed by two major world events: the 1929 Wall Street Crash, with the ensuing Great Depression that lasted until the end of the decade; and the onset of World War II in 1939. Since they are situated between the "roaring" era of the 1920s and the period of war-induced austerity of the 1940s, the 1930s are often overlooked in fashion history discussions and reduced to a mere transitional era.[4][5][6] Nevertheless, the 1930s saw many changes and innovations in fashion design, technology and consumer culture, and has been referred to as the "Design Decade" both contemporaneously and in modern times.[5][7][8] The period was also one of expansion and consolidation of the Hollywood film industry and its star system, which became a key actor in the setting and dissemination of fashion trends, a role hitherto dominated by the haute couture centered in Paris.[1][2][3]

Although the 1930s were considered a period of great modernity in clothing, the new styles were defined by a reinterpretation of the past.[9] At the beginning of the decade, the neoclassical style—so called because of its ancient Greek influence—emerged and defined the look of the period, which highlighted the natural female figure through the innovation of the bias cut.[9][10] Pioneered by couturier Madeleine Vionnet, the technique consisted of cutting the fabrics at an angle instead of in a straight line, which made them drape smoothly over the woman's figure.[9] This meant that for the first time in the history of Western fashion, dresses skimmed to the body without any sculpting underlayer.[10] Other styles that characterized the decade were romanticism, which recovered elements of Victorian fashion; and surrealism, epitomized in the work of designer Elsa Schiaparelli.[9][10]

Some of the leading fashion designers of the 1930s include the French-based Vionnet, Schiaparelli, Madame Grès, Jeanne Lanvin, Edward Molyneux, Jean Patou and Robert Piguet;[11] the British Norman Hartnell and Victor Stiebel;[12] and the Americans Hattie Carnegie, Jessie Franklin Turner, Nettie Rosenstein, Valentina, Sally Milgrim and Elizabeth Hawes, among others.[13][14] The most influential costume designer of Hollywood was Adrian, with Orry-Kelly, Travis Banton, Walter Plunkett and Dolly Tree also being prominent.[14][15] The decade was also the heyday of fashion illustrations,[16][17] as well as a time of great growth for fashion photography, with influential figures like Edward Steichen, George Hoyningen-Huene, Horst P. Horst, Louise Dahl-Wolfe, Cecil Beaton, Martin Munkácsi, Erwin Blumenfeld, George Platt Lynes and John Rawlings.[18] Some of the female fashion icons of the era include Hollywood stars such as Joan Crawford, Bette Davis, Marlene Dietrich, Vivien Leigh, Katharine Hepburn, Jean Harlow, Carole Lombard and Ginger Rogers, as well as socialites like Daisy Fellowes, Mona von Bismarck, Barbara Hutton and Wallis Simpson, who rose to fame for her relationship with King Edward VIII, a style icon in his own right.[19] Other menswear fashion icons of the 1930s were also Hollywood stars, among them Clark Gable, Gary Cooper, James Stewart, Cary Grant, Fred Astaire and Errol Flyn.[20][21]

Women's fashion

General trends

Sophistication amidst the Depression

The 1930s are well framed by two major world events: the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the outbreak of World War II in 1939, situated between the "roaring" era of the 1920s and the period of war-induced austerity of the 1940s, and defined by the decade-long severe economic crisis of the Great Depression.[4][6] While the fashion of the previous decade had been characterized by great modernity and liberation, with an emphasis on youthfulness and a straight, flat silhouette that hid feminine curves, the 1930s took off with a shift towards a more womanly and elegant form, with hemlines coming down and the waistline returning to its natural position.[5] This change in the female silhouette has often been attributed to the effects of the Great Depression, as a clear expression of the end of the Jazz Age.[5][23] For example, dress historian James Laver wrote in 1960: "It was as if fashion were trying to say: 'The party is over; the Bright Young Things are dead.' As in 1820, the return of the waist to its normal position symbolized a movement towards a new paternalism: in economic terms the American Slump; in political terms the rise of Hitler."[23] In the United States, rural populations were already making attire from recycled cotton feed sacks since the early 20th century, but the economic struggles exacerbated by the Great Depression made these "feed sack dresses" even more widespread in the 1930s, prompting companies to offer printed and better-quality options to appeal to lower-income communities.[24] The effects of the Great Depression even reached the fashion of Parisian high society, accoding to a story published by The New York Times in July 1932:

Summer soirees held in Parisian embassies, long famous for the brilliance of the women's costumes, this year reveal many gowns of the last year's vintage worn with jewels worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. The jewels remain as souvenirs of more prosperous days, while the price of a new frock is often lacking. Many of the wealthiest women who have not yet felt the pinch are dressing more simply than last year, since they feel ostentatious costume is bad taste these days. White satin gowns are favorites with many smart women for formal embassy function, since they can be worn with different jewels and varicolored wraps and slippers. They follow somewhat classic lines, which have not varied markedly within the last two years and may be worn without appearing hopelessly out of date.[25]

Although the new look of the 1930s is often described as a radical change triggered by the Great Depression, a closer inspection reveals that it was rather a continuation of trends from the late 1920s.[5] The flat, almost cubist silhouettes of the early 1920s gave way to more form-fitting shapes in the latter part of the decade; between 1927 and 1928, dresses began to follow the body's natural lines again, closely hugging the hips due to the inclusion of diagonal waist panels.[5] The waistline, which had been absent at the beginning of the 1920s and then appeared lower, returned to its natural height by the end of the decade, and hemlines, which had steadily risen to their highest point between 1925 and 1926, dropped again in 1928, often featuring floating panels at the back and sides of skirts and dresses.[5] Thus, as noted by fashion historian Emmanuelle Dirix: "even before the Crash, the main features of what we now remember as a typical 1930s silhouette were already in place."[5] Likewise, Karina Reddy of the Fashion Institute of Technology pointed out: "Despite these departures from the prevailing mode of the previous decade, the popular styles of the early 1930s were similar in their simple lines to the popular garçonne look of the twenties. But while the simplicity of the 1920s created a sack-like silhouette free from curves, the simple lines of the early thirties hugged those curves, creating a soft, feminine silhouette."[26]

It could be hypothesized that the Great Depression of the 1930s would have prompted an increase in skirt hemlines as a practical response to material scarcity, yet they remained long until the decade's end.[5] Similarly, despite rising conservative ideologies around the world, 1930s fashion notably diverged from understated and modest sartorial expressions, instead witnessing a flourishing of opulent and glamorous fashion trends that contradicted prevailing socio-political currents.[5] In the context of a 2014 exhibition focused on the decade, The Museum at FIT described it as a "startling paradox", noting that it "is a compelling irony that the elegant and progressive qualities of 1930s fashions emerged during one of the most tumultuous periods of modern Western history", and that "despite these crises—or maybe in reaction to them—the 1930s exuded an especial elegance: the blatantly beautiful neo-classic, art moderne aesthetic."[22] Likewise, Dirix wrote: "This is what is so intriguing about a fashion study of the 1930s—it allows us to see that whilst fashion may be inextricably bound up with culture, the way it influences and is influenced by the world is neither obvious nor overtly logical. To understand fashion one not only has to look at the culture that produced and consumed it, but one also has to be able to 'read' the garments themselves."[5]

The bias cut and neoclassicism

Although the decade saw the return of natural waistlines and longer skirts and sleeves, fashion historian James Laver noted that "there is no exact parallel between the fashions of the early 1930s and those of a century before, for the waist did not become excessively tight and the general lines of the skirt remained more or less perpendicular."[23]

Crucial to this new silhouette of the early 1930s was the so-called bias cut technique, which involved "cutting fabric on the bias at a 45 degree angle on the woven fabric against the weave".[1][26] The bias cut was championed by French designer Madeleine Vionnet in the 1920s and, by the early 1930s, it became a popular style for creating garments that lightly hugged a woman's curves, contributing to the overall slender look of the era.[1][26] In particular, the body-skimming style dominated eveningwear, characterized by satin dresses with low backs that hugged the body's curves and flared at the bottom, creating a "fluid and feminine silhouette".[1][26]

The predominant fashion trend of the early 1930s was the so-called neoclassic style, which drew inspiration from classical Greece.[27] Neoclassical fashion was defined by "white and ivory columnar bias-cut evening dresses [that] often featured Greek details such as cowl or cascade drapes."[27] Fashion publications compared garments to Greek architecture, while editorials frequently juxtaposed models with ancient columns and sculptures.[27] One of the most notable proponents of this style was French designer Augusta Bernard, who was known for her expertise with the bias cut.[27]

Although the Art Deco style is generally considered to have reached its peak in the 1920s, it continued into the 1930s as an element of the "modernist aesthetic" that was popular in clothing and textile design.[28]

The ballerina skirt—a "wide skirt, often of several layers of light fabric, of mid-calf length and inspired by classical ballets"—was especially popular during the 1930s.[29]

For evening attire, the "erogenous zone" moved to the back, with gowns crafted to showcase deep, open backs or no back at all.[30]

Hollywood glamour

We, the couturiers, can no longer live without the cinema any more than the cinema can live without us. We corroborate each other's instinct.

The concept of glamour became ubiquitous in the 1930s,[31] and the decade has been described as the "Golden Age of Glamour".[4][32] As noted by Stephen Gundle, the "[glamour] phenomenon became so widespread that it was freely attached to the most diverse people and roles", as the term was even extended to designate men or boys.[31] The main driver of fashion for glamour was the Hollywood film industry, as women around the world sought to integrate elements of the movie stars into their personal styles.[31][1] Actresses such as Jean Harlow, Joan Crawford, Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich and Bette Davis became some of the first style icons of Hollywood and had a direct influence on fashion,[1] beginning to replace the traditional role of the upper classes as leading trendsetters.[2] The effects of the Great Depression solidified Hollywood's role in fashion, as studios reframed celebrity as a relatable yet heightened ideal, fully integrating glamour into American culture and shifting its perception from a foreign concept to a domestic product.[31] This transformation peaked as glamour became a central commodity for Hollywood, offering the public an escape from widespread poverty.[31] Studio publicity teams capitalized on this by promoting the idea that women could model their appearance after a star with comparable physical traits or personality.[31] To support this trend, fashion and beauty advice attributed to actresses appeared frequently in magazines and retail outlets, while pattern companies produced affordable versions of film costumes for public consumption.[31] In its early years, Hollywood relied on European theatrical costumes and Parisian haute couture due to a lack of confidence in shaping fashion trends, but this dependence was a transitional phase that allowed it to eventually become a dominant force in glamour by the 1930s.[31]

During an era when brand names held minimal influence, film stars emerged as key drivers of fashion innovation.[31] Their attire—featuring costly materials, unique designs, and luxurious furs—conveyed associations with high society, European sophistication, and exclusivity, captivating audiences with its aspirational appeal.[31] The immense popularity of these stars enabled them to penetrate fashion magazines previously reserved for social elites, reshaping the industry's dynamics.[31] Unlike traditional aristocrats, American film stars presented an attainable ideal, blending exaggerated femininity with a relatable persona, inspiring admiration and emulation among audiences.[31] As noted by Stephen Gundle, Hollywood pioneered a distinctive style that blended high fashion, mass spectacle, and accessible streetwear, creating a reproducible yet theatrical aesthetic.[31] Hollywood's rise as a fashion influencer was bolstered by the need for designers to craft forward-thinking outfits that would remain cutting-edge by a film's release date.[3] These styles were subsequently replicated by retailers, prompting American design to diverge from Parisian influence.[3] For instance, the "historical" couture trends of the 1930s drew inspiration directly from Hollywood’s costume creations.[3] Notably, designer Elsa Schiaparelli created a collection based on actress Mae West's signature look.[31] A paradigmatic example of Hollywood's influence on 1930s fashion was the white cotton organdie gown designed by Adrian and worn by Joan Crawford in the 1932 film Letty Lynton, which sparked a wave of greatly popular copies across various price ranges.[3][25] Since then, the dress is regarded as one of the most iconic in history.[19][33] In addition to Adrian, other influential Hollywood costume designers of the era included Edith Head, Travis Banton and Walter Plunkett.[3] Anna May Wong—the first Chinese American Hollywood star—was considered one of the best-dressed women in the world, although her outfits were unconvential, combining current Western fashions with traditional Chinese dress.[34] She was especially associated with the cheongsam dress, which she helped popularize as a staple.[34] Her hairstyle was also widely imitated, featuring straight-cut bangs.[34] Wong may be considered the first fashion icon of Asian descent, and is said to have "opened the door to more inclusive standards."[34]

Romanticism and surrealism

As eveningwear leaned toward sleek, form-fitting designs, daywear fashion "returned to romanticism and femininity".[26] Daytime dresses showcased an array of patterns—including florals, plaids, polka dots and bolder, abstract styles.[26] These dresses featured well-defined waists and lengths that hovered between mid-calf and just above the ankle.[26] Tailored suits, sharp and structured, gained favor with their clean lines and bold, sculpted shoulders.[26] The dramatic shoulder, a signature of 1930s style, was achieved with padding, layered fabrics, or decorative touches, adding flair to both suits and dresses.[26]

Adrian's white mousseline de soie gown for Joan Crawford in the 1932 film Letty Lynton is widely credited with starting the trend for "romantic nostalgia".[35] The dress, featuring striking, oversized ruffled sleeves, sparked a wave of copies across various price ranges.[25]

As noted by the Smithsonian's Fashion: The Definitive History of Costume and Style: "Robes de style (with loose bodices, dropped waists, and full skirts) had preserved prettiness and the traditional idea of femininity throughout the 1920s. Now diaphanous concoctions trimmed with an abundance of frills, ruffles, and lace became popular with those too young, too old, or not streamlined enough to squeeze their bodies into an unforgiving lamé or satin sheath."[35] This new wave of romanticism was boosted by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth's state visit to Paris in July 1938.[36] Known as the "White Wardrobe", the famous series of romantic gowns she wore during the visit were based on the paintings by Franz Xaver Winterhalter.[35] Reflecting on the romantic fashion of the 1930s, Cecil Willett Cunnington wrote in 1952: "Never has Fashion been more ironic than in this attempt to revive, for an evening dress, the modes current on the eve of the Franco-Prussian War."[36]

Other influences

In addition to the influence of Hollywood, European royalty, former royals and members of café society continued to play an important role in shaping fashion trends throughout the Western world, just as they did in the 1920s.[37] A key figure in this sphere was Edward VIII, who ascended to the British throne on 20 January 1936 but abdicated on 11 December 1936, to marry Wallis Simpson, an American divorcée, after which they became the Duke and Duchess of Windsor following their wedding on 3 June 1937.[38] The couple emerged as one of the most prominent fashion icons of the 1930s and were key trendsetters for the high society of the era, as their cultivation of style became a vocation amid a life of enforced leisure post-abdication.[38] Simpson epitomized the disciplined, "hard chic" of the decade with her restrained ensembles from designers like Mainbocher, Schiaparelli, and Balenciaga, notably wearing a simple pale blue Mainbocher dress dyed to match the wedding chapel's interior for their nuptials.[38] She was also photographed by Cecil Beaton in 1937 wearing a Schiaparelli dress, designed in collaboration with Salvador Dali, depicting a lobster, whose placement was said to have had great sexual connotations that were seen as scandalous at the time.[19] French designer Roland Mouret once remarked: "Love her or hate her, the world is still obsessed by that woman."[19]

Another style icon of the decade was Daisy Fellowes, a fixture on the social scene and heiress turned Paris editor of Harper's Bazaar, who was as famous for her dazzling jewelry obsession as she was for her headline-grabbing romantic exploits.[19] Her flair for 1930s fashion led her to champion designers like Schiaparelli, who reportedly crafted her iconic "shocking pink" in her honor, while Cartier adorned her with treasures fit for her extravagant taste.[19] There was also Mona von Bismarck, the American socialite whose wardrobe and penchant for older suitors made her a precursor to modern celebrities.[19] Crowned the "Best Dressed Woman in the World" in 1933 by luminaries like Chanel and Vionnet, and later enshrined in the International Best Dressed List Hall of Fame in 1958, her devotion to couture was so profound she reportedly mourned in bed for three days when Balenciaga shuttered his atelier in 1968.[19] Another influential socialite was Barbara Hutton, heiress to the Woolworth fortune, who reigned as the ultimate "poor little rich girl", with her lavish global party-hopping and a Depression-era debutante ball cementing her notoriety.[19] Her true legacy, however, lay in her jewelry collection—featuring jade, Cartier pieces, and a pearl necklace once worn by Marie Antoinette—a trove that outshone even her immense wealth.[19]

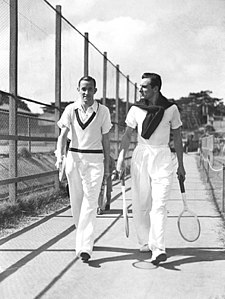

Parallel to royal influence, the repeal of Prohibition in 1933 spurred the rise of glamorous nightlife hubs in New York City, such as El Morocco, 21, and the Stork Club, alongside Harlem's Savoy Ballroom and Cotton Club, where couples danced to swing music by Duke Ellington and Count Basie.[38] In London, society revolved around theater evenings, dinners at the Savoy Grill, and screenings at the Curzon Cinema, while Paris' international café society frequented clubs like the Le Bœuf sur le toit.[38] Wealthy Americans and Europeans, photographed at fashionable resorts, further popularized sportswear for exclusive activities like tennis, riding, and skiing—pursuits largely inaccessible during the Great Depression.[38] Concurrently, cruise ships offered luxurious travel to exotic destinations like India, New Zealand, and South America, promoted through evocative advertising.[38] The public's fascination with high society extended to debutantes, whose lavish coming-out parties dominated gossip columns in the late 1930s.[37] In London, Margaret Whigham, daughter of a rayon tycoon, was named "Deb of the Year" in 1930, while in the U.S., Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton's 1932 debut featured four orchestras and singer Rudy Vallée.[38] Brenda Frazier, a media favorite dubbed a "celebutante", appeared on the cover of Life magazine in 1938 and popularized the strapless evening gown.[38][37]

End of decade styles

In the summer of 1939, a reported from Vogue noted the wide variety of models offered by the leading fashion houses: "Nothing varies more than silhouette. You can look as different from your neighbour as the moon from the sun—and both of you are right. The only thing that you must have in common is a tiny waist, held in if necessary by super-light weight boned and laced corsets. There isn't a silhouette in Paris that doesn't cave in at the waist."[36]

The greatest textile innovation of the decade was nylon, which appeared in 1939 and revolutionized hosiery.[18]

Sportswear

https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2016/02/160202_cultura_pijamas_moda_finde_vs

-

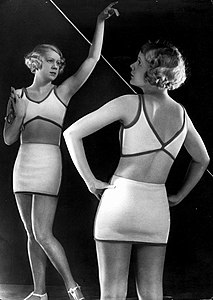

Fashion shoot for bathing suits photographed by Yva, c. 1930.

-

Argentine swimmers Alicia Laviaguerre and Jeannette Campbell in El Gráfico magazine, 1931.

Accessories

In the 1930s and its Great Depression context, fashion accessories were seen as an inexpensive option to elevate and modernize an existing outfit.[39] Women under a budget could accessorise their dresses with a variety of "cheap yet glamorous ready-made articles such as diamanté dress clips, bracelets, brooches and necklaces, embroidered handbags, furs, fancy footwear and modern hats, that were available in great variety from most catalogue companies."[40] Gloves were also a central element of a fashionable look; elbow-length models were used to accompany evening dresses, while short or opera-length styles, made of fabric or leather, were chosen for daytime attire.[40] Buttons were also of great importance and were generally large or of decreasing size, some featuring surrealist motifs (like cicadas, butterflies and dragonflies), and others made of fabric from the patterns on the dresses.[20] Manufacturers and retailers launched matching sets of hats, gloves, bags, and shoes in bold colors.[40] Handbags of the 1930s remained similar to those of the 1920s; at the beginning of the decade beaded or enamelled mesh models were popular, while at the end of the decade the use of leather became increasingly widespread.[40]

Hats were a vital element of a woman's wardrobe in the decade, and thus received more editorial coverage than any other type of accessory.[39] The 1930s marked the end of the dominance of the tight-fitting, deep-crowned cloche hats that defined the previous decade, being replaced with a wide variety of designs.[39][41] Vogue magazine declared 1931 as the "Great Hat Year" because of the variety of novel models and the fact that "they were a considerable factor in stemming the tide of depression that was another phenomenon of that momentous year."[39] The choice of headgear allowed women to update or add formality to an outfit, as well as reflect their personality.[39] Hollywood stars were a major influence in popularizing new hat styles, especially Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich.[41] The Gilbert Adrian-designed hat worn by Garbo in the 1930 film Romance, known as the Empress Eugénie hat, "set off a nation-wide buying craze, as did the wide-brimmed slouch hat that Garbo would wear to hide her face."[41]

To complement the new "diagonalistic" and body-hugging shapes of the fashionable bias-cut clothing, various styles of hats were designed to be worn at different angles over the head and forehead, evoking the movement of the gowns as well as some styles of men's hats.[39] As noted by Colleen Hill: "By the early 1930s, newly 'masculine' hat styles began to make regular appearances in fashion editorials. Sometimes resembling a man's bowler, other times paying closer homage to the fedora, they shared a quality of casual elegance, and could be paired with almost any daytime ensemble. (...) Rarely were any of these hats mere copies of menswear styles, however. Although not as severely modern as the cloche, their intricate folds, tucks, and stitching techniques were fresh and subtly complex."[39] Although no single initiator of this trend can be identified, as early as the 1920s several manufacturers of men's felt hats began to offer models for women in response to the popularity of cloche hats[39] By 1936, a noticeable shift occurred in hat trends, as the once prevalent simple, masculine styles made room for designs boasting strikingly different silhouettes.[39] Fashion editorials showcased hats with exaggerated crowns, some lavishly adorned with draped fabrics or intricate trimmings, while others seamlessly integrated elements of earlier streamlined designs with the fresh silhouette.[39]

The 1930s saw the return of trimmings such as flowers and feathers in millinery after their near-disappearance in the second half of the 1920s.[39] Nevertheless, they were "markedly simpler than the elaborate embellishments seen on hats prior to World War I."[39] The decade also marked the emergence of prominent American milliners such as Lilly Daché, Mr. John and Sally Victor, who appeared in fashion magazines alongside French designers.[41] Mr. John designed various iconic hats for Hollywood films, notably a veiled cloche worn by Dietrich in Shanghai Express—which made veils popular nationwide—and the famous cartwheel hat worn by Vivien Leigh in Gone with the Wind (1939).[42] However, the designer who most epitomized the 1930s was Schiaparelli.[43] Some of her most emblematic designs of the decade were the "Mad Cap", which consisted of a "simple knitted cap that could be twisted into a variety of shapes"; and her 1935 doll hat, which "perched whimsically on the front of the head and was secured by a band, elastic, or a snood" that "covered and contained the hair on the back of the head".[43] Schiaparelli was known for often incorporating surrealist influences into her headgear designs, such as hats in the shape of inkwells, baskets of flowers or lamb chops.[43] One of her most iconic designs was the "Shoe Hat" made in collaboration with the surrealist Salvador Dalí, which "looked like a high-heeled shoe worn upside down on the head."[43] The influence of Schiaparelli's surrealism was picked up by Hollywood, such as in the "tower" hat worn by Garbo in Ninotchka (1939).[43]

The 1930s featured a wide variety of shoe and heel shapes to choose from, especially by the end of the decade,[44] ranging from flats and pumps to lace-ups, ankle-straps, and models with buckles.[40] In addition, the early 1930s marked the arrival of low-heeled "Spectator" brogues and other styles of two-toned shoes.[40] Strapless opera pumps became more common for daily use, replacing shoes with straps.[44] Despite this shift, "sandals" (strap-adorned pumps) were still worn for summer and dancing.[44] Decorative elements often included contrasting color piping or metallic leather.[44] Practical daywear options included high vamp shoes known as "slip-ons" or "step-ins," and lace-up styles called Oxfords.[44] The introduction of wedge heels and open-toe styles foreshadowed the trends of 1940s fashion.[44] The late 1930s also saw the introduction of the platform shoe, credited to Italian designer Salvatore Ferragamo.[45]

Hair and cosmetics

The 1930s saw a rise in makeup and the beauty industry, spurred in part by Hollywood's film industry, which led to a growing abundance of cosmetics, such as perfumes and nail polishes, becoming more widely available.[26][30] This allowed women to copy their favorite movie stars at a small cost, as Cally Blackman noted: "Every woman could imitate and buy into, at relatively little cost, the look of her favourite stars, if only through copying their makeup and hairstyles: cinema democratized the empire of fashion by making glamour accessible."[26] During the decade, beauty salons became an "integral part of a woman's ritual of beauty".[46] Embracing the growing fashion for exercise and wellness, cosmetic companies like Elizabeth Arden expanded their services for women in the 1930s to also include fitness studios within the beauty salons.[47]

The androgynous style popular among women in the 1920s, characterized by short, cropped hair, gave way in the 1930s to longer locks that were increasingly styled in elegant updos as the decade progressed.[30] The predominant style in the early 1930s consisted of short hair styled with soft waves.[26] A defining beauty trend of the era was pencil thin eyebrows, which were either heavily plucked to form a line or removed altogether and drawn on with pencil.[47]

In the 1930s, makeup was much softer and natural than the "vampy" style of the 1920s, especially around the eyes, abadoning the dramatic, dark, kohl-rimmed eyes sported by silent movie stars.[47] Instead, women applied a range of colors over and just beyond the lid, with the palette of the period consisting of blues, greens and even shimmery golds and silvers.[47] Rouge also took on a more subdued role, shifting away from the stark pale skin and bold, circular cheek color favored by flappers in the 1920s.[47] Instead, it was applied lightly to sculpt the face with gentle contours and a soft flush, creating a vibrant, healthy glow, a change that echoed the 1930s focus on vitality and wellness.[47] Meanwhile, a tanned complexion started to gain popularity, inspired by Coco Chanel's influence.[47] In addition, the small rosebud-shaped lips of the 1920s gave way to the 1930s more natural lip shape, painted in a range of colors that included strong reds as well as lighter, more neutral tints.[47] From the 1920s onward, mascara emerged as a key tool in a woman's makeup collection, enhancing and accentuating the eyes.[47] During the 1930s, it was available as a solid block paired with a brush, as liquid mascara did not make its debut until the 1950s.[47] Nail polish was typically applied to match the colors of the makeup on the face, and the "moon manicure" was a popular design during the era, in which either the tip or "moon" of the nail or both remained unpainted.[47]

Undergarments

The 1930s marked a transformative period in the history of women's undergarments, reflecting both technological advancements and shifting cultural ideals of femininity and bodily aesthetics. Emerging from the 1920s, when the fashionable silhouette favored a slender, almost boyish figure with minimal bust emphasis, the new decade ushered in a preference for a structured, uplifted, and separated bust, fundamentally altering the purpose and design of undergarments.[48] Initially patented in 1914, the brassière—a word already in circulation by the early 1900s—truly evolved during the decade.[49] This shift saw the brassière—often shortened to "bra" by the mid-1930s—evolve from a simple flattening device into a garment designed to lift and shape the breasts, a change driven by designers' focus on accentuating the upper torso through innovative neckline details and longer hemlines that redirected attention upward.[49][48] The term "bra" gained widespread acceptance, with a 1934 Harper's Bazaar survey noting its prevalence among college women, signaling a linguistic and cultural consolidation of this new undergarment identity.[50]

Technological innovation played a critical role in this evolution, as the 1930s introduced materials like man-made fibers, durable elastics, and notably Lastex—a rubber-based thread developed by Dunlop chemists, extruded into fine filaments and wrapped in cotton, silk, or rayon to enhance comfort and elasticity.[48][51] Lastex revolutionized bras and girdles, offering flexibility and support without the heavy boning of previous decades, aligning with the decade's demand for garments that accommodated increased physical activity, such as the energetic dance styles of the Lindy Hop and Quickstep popular in the era's dance halls.[48] By 1938, nylon emerged as another groundbreaking material, initially used in toothbrushes but soon adopted for bras, stockings, and other undergarments due to its strength and lightweight properties, with its commercial application in stockings debuting in 1940.[48] Alongside these material advancements, standardization in sizing emerged: in 1932, bras began to be categorized into A, B, C, and D cups with numerical band sizes (e.g., 34, 36, 38), while Maidenform introduced a sizing system based on breast volume in ounces, improving fit precision and comfort.[51]

The bra's design also progressed significantly, with the introduction of structured cups—often triangular or conical—crafted from bias-cut fabric or stabilized by "whirlpool stitching", a technique of concentric topstitching that eliminated under-cup seams and enhanced adaptability to individual breast shapes.[48][52] This focus on lift and separation contrasted sharply with the 1920s bust-suppressing styles like the Symington side lacer, reflecting a broader rejection of the androgynous flapper ideal in favor of a more defined feminine silhouette.[51] Bras became essential for complementing the decade's fashion trends, such as higher-waisted dresses and bias-cut evening gowns, which demanded smooth contours and nicely shaped breasts.[53] Specialty designs also appeared, including bras with versatile straps to suit low-backed or shoulder-baring dresses, catering to the elegance of 1930s evening wear.[53]

Beyond bras, women's undergarments in the 1930s encompassed a range of foundation garments designed to sculpt the figure beneath the decade's lean yet shapely ideal. Girdles, resembling snug skirts that extended over the stomach and buttocks, replaced the rigid corsets of earlier eras for many women, leveraging Lastex and two-way stretch elastic to smooth the silhouette without cumbersome fasteners.[52][53] For those requiring more robust support, corselettes—boned garments extending from the shoulders to the upper thighs—offered comprehensive shaping of the bust, stomach, and hips.[52] Circular knitting machines further enabled the production of seamless girdles, enhancing comfort and practicality, while slide closures in foundations reflected additional mechanical ingenuity.[48][53] Slips remained a staple, worn over other undergarments to eliminate visible lines, though some featured built-in bras or control panels for a sleeker effect.[52][53]

Pant styles diversified as well, with bloomers retaining their high elastic waists and above-the-knee length from the 1920s, while step-in panties offered a looser fit with flared legs varying from brief to mid-thigh, and briefs provided a closer-fitting, high-waisted option extending just past the buttocks.[52] Stockings, typically made of silk or rayon until nylon's 1939 introduction, were worn in skin-tone shades or with decorative clocks and patterns, their sizing refined to match the mid-calf hemlines of daywear.[53] Meanwhile, camisoles, tap pants, and wide-legged silky pajamas catered to both practical and leisurely needs, the latter doubling as loungewear and influencing outer fashion with their boudoir aesthetic.[53]

Economically, the Great Depression shaped undergarment consumption, yet bra sales surged despite widespread unemployment, reflecting their affordability—Sears, Roebuck catalogs in 1935 offered bras for as little as $0.14 compared to $4–$6 corsets—and their role in maintaining a groomed appearance during trying times.[48] This accessibility contrasted with the 1920s, when corset sales had declined by a third between 1920 and 1928 as bras gained traction, a trend accentuated in the 1930s by the bra's newfound prominence.[51] For wealthier women or those embracing minimalism, some forwent undergarments entirely beneath soft, bias-cut evening wear to achieve a neoclassical silhouette free of visible lines, though most relied on foundations to meet fashion's exacting standards.[53]

-

A corset from a 1930 catalogue, designed for those who wish to reduce the hips and flatten the abdomen.

-

Brassiere and girdle from a 1933 catalogue.

-

A corset from a 1933 catalogue.

-

A maternity support undergarment from a 1933 catalogue.

Men's fashion

General trends

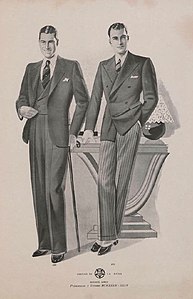

In the 1930s, Savile Row tailoring continued to dominate menswear trends.[10] Matching the shift in womenswear's silhouettes, men's suits "were worn with semi-accentuated waists", with a slimmed down silhouette that contrasted the" looser, baggy fits of the 1920s".[10] Edward VIII, then Prince of Wales, was a major fashion icon in menswear, epitomizing the English style.[10] English conservative politician Anthony Eden was also fashion leader, with his trademark look consisting of a white linen waistcoat worn with a lounge suit and his signature silk-brimmed homburg hat, which known as "the Anthony Eden".[54]

For a brief period during the decade, the tailless "mess jacket"—based on the military mess dress uniform—was worn as an alternative for the white dinner jacket during hot weather.[55]

As with women, Hollywood stars played a leading role in men's fashion of the decade, especially Clark Gable, who popularized sport coats; Gary Cooper, who made two-tone shoes fashionable; and Errol Flynn.[20]

http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/h/history-of-fashion-1900-1970/

https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-decade-of-defiance-1392756874

-

A man in Hungary, 1930.

-

Lithuanian diplomats Dovas Zaunius and Vaclovas Sidzikauskas, 1932.

-

A young man in Amsterdam, 1932.

-

French athlete André Dubonnet in 1933.

-

A yougn man in Hungary, 1933.

-

Argentine fashion plate from 1934.

-

Dick Powell in Radio Stars magazine, 1934.

-

A man throwing the trash in Downtown Seattle, 1936.

-

Architects Angelo Bianchetti and Le Corbusier, 1937.

-

Norwegian politician Kjeld Stub Irgens in his garden, 1939.

Undergarments

Children's fashion

Fashion media

Illustration

-

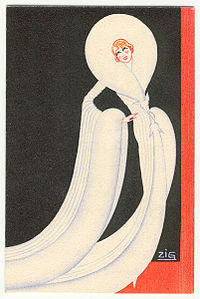

French actress Mistinguett depicted in an advertisement, c. 1930.

-

Fashion plate from the Netherlands, May 1931.

-

Fashion plate from France, November 1931.

-

Fashion plate from France, March 1932.

-

Fashion plate from France, June 1932.

-

Fashion plate from the Netherlands, March 1935.

Image galleries

Womenswear

-

Evening coat by Revillon Frères made of fur, 1930.

-

Evening dress from France made of bead-embroidered silk, c. 1930.

-

A young typewriter in the Netherlands, 1931.

-

An opera cloak from France made of silk velvet, embroidered with beads, sequins, and rhinestones, 1931.

-

English aristocrat Diana Mosley, 1932.

-

Evening coat by Jeanne Lanvin made of wool and fur, 1932.

-

A group of women at a horse race in Brisbane, 1933.

-

A group of working women leaving the factory in Buenos Aires, 1933.

-

Portrait of a young woman in Romania, c. 1930s.

-

Irene Dunne in a 1934 publicity still.

-

Evening jacket by Jeanne Lanvin made of silk, fur and metallic thread, 1936.

-

Portrait of a lady by Bernard Boutet de Monvel, 1936.

-

Romantic-style dress by Jeanne Lanvin made of cotton and silk, 1937.

-

A woman attending a race at the Randwick Racecourse in Sydney, 1937.

-

Evening dress by Bergdorf Goodman made of silk, velvet and metallic thread, 1937

-

People dancing the jitterbug in New York City, 1938.

-

Farouk of Egypt with his mother and sisters, 1938.

-

Two women in Budapest, 1939.

-

Marlene Dietrich in the 1930 film Morocco, wearing her signature masculine attire, featuring a white tie and top hat.

-

Joan Crawford in the 1932 film Letty Lynton, wearing the influential chiffon dress by Adrian that created a craze for similar designs.

-

Barbara Stanwyck in the 1933 film Baby Face, wearing a nightgown designed by Orry-Kelly that features a plunging back.

-

Asian-American fashion icon Anna May Wong in the 1934 film Limehouse Blues, wearing a reintepretation of the Chinese cheongsam designed by Travis Banton.

-

Carole Lombard in the 1935 film Rumba in a Travis Banton design, showcasing the neoclassical aesthetic of the decade.

-

Ginger Rogers in the 1936 film Swing Time, wearing a silk nightgown and matching cape designed by Bernard Newman.

-

Nina Mae McKinney—one of the first African-American Hollywood actresses—c. 1936, wearing hoop earrings and a floral print ensemble.

-

Katharine Hepburn during the filming of the 1938 film Bringing Up Baby. She pioneered the use of pants on women and helped popularize them.

-

Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford and Rosalind Russell in the 1939 film The Women, wearing nightgowns designed by Adrian

Hats

-

Parisian fashion plate, 1931.

-

Wool hat by Jeanne Lanvin, 1932.

-

German actress Renate Müller, 1932.

-

Swedish actress Dora Söderberg, 1933.

-

Cadanian athlete Alexandrine Gibb, 1934.

-

Three models in a fashion show for hats in Paris, 1936.

-

Parisian fashion shoot, 1936.

-

Parisian fashion shoot, 1936.

-

Parisian fashion shoot, 1936.

-

Parisian fashion shoot, 1936.

-

American entertainer Gypsy Rose Lee wearing a Eugénie hat, 1937.

-

Berliner fashion shoot by Yva, c. 1938.

-

A woman in Budapest, 1938.

-

Swedish fashion shoot, 1939.

Shoes

-

Calf-high lace-up boots in brown leather, c. 1925–1935.

-

Brown leather shoes with decorative plastic buckle, c. 1930–1932.

-

Silk shoes with rhinestone decoration, c. 1932.

-

Silk and leather evening shoes, c. 1933.

-

High heeled platform shoes covered in snakeskin leather, c. 1930s.

-

Silver dancing shoes, c. 1935–1940.

-

White linen summer shoes, c. 1935–1940.

-

White nubuck lace-up shoes with decorative holes, c. 1935–1940.

-

Red suede shoes with dark blue leather trims, c. 1938–1940.

-

gold-plated leather sandals, c. 1937–1940.

-

Leather sandals, c. 1938.

-

Leather evening shoes, featuring drawstrings with tassels, c. 1938–1940.

-

Black leather lace-up ankle boots, c. 1938–1940.

-

Blue-black crocodile leather shoes, c. 1939.

Children's fashion

-

1931

-

1- Girl's dress 1931

-

6- Between 1932 and 1935

-

Girls at a Shirley Temple lookalike contest in Sydney, 1934.

-

3-1939

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Thomas, Heather (July 20, 2021). "Women's Fashion History Through Newspapers: 1921-1940". Headlines and Heroes. Library of Congress. ISSN 2692-2177. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c Berry 2000, p. XII.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hennessy & Fischel 2012, p. 306.

- ^ a b c d "The Golden Age of Glamour". The Lady. 2021. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Fiell 2021, p. 9.

- ^ a b Bumpus, Jessica (March 18, 2019). "Los años treinta: la década que la moda ignoró (hasta ahora)". Vogue España (in Spanish). Condé Nast. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ "Index". Design Decade 1930-1940 (Special issue of The Architectural Forum). Vol. 73, no. 4. Philadelphia: Time, Inc. October 1940. ASIN B004XU60RK.

- ^ Buchanan, Richard (1990). "Myth and Maturity: Toward a New Order in the Decade of Design". Design Issues. 6 (2). MIT Press: 70–80. Retrieved May 24, 2022 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c d e Andrew Yamato (February 17, 2014). Elegance in an Age of Crisis, Part 1: Hers (YouTube video). The Museum at FIT. Retrieved May 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Ramzi, Lilah (April 5, 2024). "A 1930s Fashion History Lesson: Goddess Gowns, Surrealism, and More Trends of the Escapist Era". Vogue. Retrieved May 11, 2024.

- ^ Cole & Deihl 2015, pp. 173–178.

- ^ Cole & Deihl 2015, p. 179.

- ^ Cole & Deihl 2015, p. 180.

- ^ a b Cole & Deihl 2015, p. 182.

- ^ Cole & Deihl 2015, p. 184.

- ^ McKelvey, Kathryn; Munslow, Janine (2007) [1997]. Illustrating Fashion. Blackwell Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 9781444313017. Retrieved May 20, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ Zeegen, Lawrence; Crush (2005). The Fundamentals of Illustration. Lausanne: AVA Publishing. p. 96. ISBN 9782940373338. Retrieved May 20, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Cole & Deihl 2015, p. 164.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "The iconic beauties who perfectly sum up 1930s style". Marie Claire. March 3, 2017. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Saulquinwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cole & Deihl 2015, p. 187.

- ^ a b "Elegance in an Age of Crisis: Fashions of the 1930s". The Museum at FIT. 2014. Retrieved May 18, 2024.

- ^ a b c Laver 1960, p. 240.

- ^ Brandes, Kendra (2009). "Feed Sack Fashion in Rural America: A Reflection of Culture". Online Journal of Rural Research & Policy. 4 (1). New Prairie Press, Kansas State University. ISSN 1936-0487. Retrieved May 18, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Tortora & Marcketti 2015, p. 460.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Reddy, Karina (April 5, 2019). "1930-1939". Fashion History Timeline. History of Art Department. Fashion Institute of Technology. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Cole & Deihl 2015, p. 165.

- ^ Cumming, Cunnington & Cunnington 2010, p. 8.

- ^ Cumming, Cunnington & Cunnington 2010, p. 11.

- ^ a b c "Women's Fashion in the 1930s". Brighton Museum. 26 February 2015. Archived from the original on 18 June 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Gundle, Stephen (2009). Glamour: A History. Oxford University Press. p. 185–198. ISBN 9780191623370. Retrieved May 20, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ Fiell 2021, Preface.

- ^ Avello, Iván (11 June 2019). "7 vestidos (y un pantalón) que han hecho historia". Harper's Bazaar (in Spanish). Spain. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ a b c d Cole & Deihl 2015, p. 183.

- ^ a b c Hennessy & Fischel 2012, p. 291.

- ^ a b c Laver 1960, p. 248.

- ^ a b c Tortora & Marcketti 2015, p. 464.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cole & Deihl 2015, p. 163.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n ""Great Chic from Little Details" – 1930s Millinery". The Museum at FIT. April 22, 2014. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Fiell 2021, p. 22.

- ^ a b c d Blanco F. 2016, p. 163.

- ^ Blanco F. 2016, p. 163–164.

- ^ a b c d e Blanco F. 2016, p. 164.

- ^ a b c d e f Hennessy & Fischel 2012, p. 273.

- ^ "Salvatore Ferragamo | Sandals". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Turk, Rose-Marie (12 January 1995). "A Brief History of Hair : Dyeing. Bleaching. Coating with lard! What some women through the years have done--and will do--for a 'do". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hibbard, Ruth (August 8, 2018). "Giving face – women's make-up style and status in the 1930s". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wood, Carol (1 November 2013). "Bra Support Comes of Age: The history of the bra, 1920-1930". Finery. Greater Bay Area Costumers Guild (GBACG). Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ^ a b Hennessy & Fischel 2012, p. 277.

- ^ Hennessy & Fischel 2012, p. 270.

- ^ a b c d Singer, Olivia (24 November 2015). "The Brassiere: An Uplifting History". Another Magazine. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ^ a b c d e "A Brief History of Women's Undergarments". Museums of Western Colorado. 9 March 2024. Archived from the original on 20 August 2024. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cole & Deihl 2015, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Hennessy & Fischel 2012, p. 288.

- ^ Hennessy & Fischel 2012, p. 289.

Bibliography

- Berry, Sarah (2000). Screen Style: Fashion and Femininity in 1930s Hollywood. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816633128.

- Blanco F., José, ed. (2016). Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe. Vol. 3. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-161-069-310-3. Retrieved May 12, 2024 – via Google Books.

- Cumming, Valerie; Cunnington, C. W.; Cunnington, P. E. (2010). The Dictionary of Fashion History. Berg Publishers. ISBN 9781847885340.

- Cole, Daniel James; Deihl, Nancy (2015). The History of Modern Fashion. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 9781780676036.

- Fiell, Charlotte, ed. (2021) [2011]. 1930s Fashion Sourcebook: The Definitive Sourcebook (eBook). Preface by Charlotte Fiell. Introduction by Emmanuelle Dirix. Welbeck Publishing. ISBN 9781802791631. Retrieved May 19, 2024 – via Google Books.

- Hennessy, Kathryn; Fischel, Anna, eds. (2012). Fashion: The Definitive History of Costume and Style. Smithsonian. DK. ISBN 9780756698355.

- Laver, James (1960). The Concise History of Costume and Fashion. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ASIN B000WONVOG.

- Tortora, Phyllis G.; Marcketti, Sara B. (2015) [1989]. Survey of Historic Costume (6th ed.). Fairchild Books. ISBN 978-1-62892-167-0.

https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=RchiAgAAQBAJ&dq=%221930s+fashion%22&hl=es&source=gbs_navlinks_s

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/05/the-way-we-look-now/359803/

https://screenarchive.brighton.ac.uk/portfolio/screen-search-fashion/1930s-fashion/1930s-womenswear/

http://www.magicasruinas.com.ar/revistero/argentina/argentina-moda-30s.htm

https://journals.openedition.org/apparences/1359?lang=en

Body ideal https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/38932032.pdf

External links

Media related to 1930s fashion at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to 1930s fashion at Wikimedia Commons